The Favorite–Longshot Bias in Tennis: Evidence from 40,000 Matches

After analyzing all the ATP matches bets from 2010 to 2025, the conclusion is clear: betting too much on longshots is disastrous long run.

In a previous article — which you can read here — I introduced the concept of the Favorite–Longshot Bias: what it is, why it exists, and why every serious bettor should understand it. In this new piece, I move from theory to evidence. Here, I put numbers behind the idea and show how the Favorite–Longshot Bias actually behaves in real tennis markets.

2025: A Truly Atypical Season

First, I took all the ATP matches (main draw) of 2025 and looked at how favorites and underdogs performed over the season using Pinnacle’s closing odds and a flat-stake approach; that is, we assume a constant stake of 1 unit on the favorite and 1 unit on the underdog in every match.

Pinnacle closing odds are the most accurate estimator of the true odds, so I will always use their odds in my analysis.

And this is what I got:

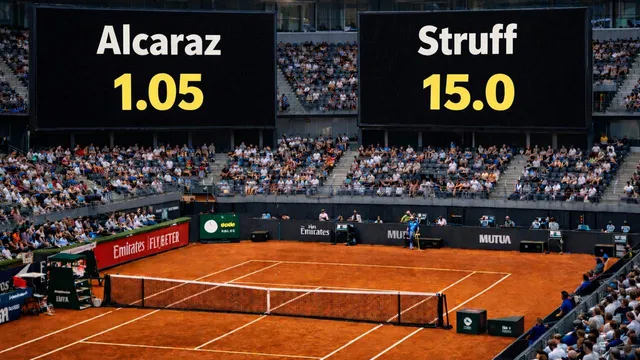

Well you can see that favorites ended the season with a yield of about 80 units, what is a –3.1% yield/ROI, while underdogs lost 21 units, a yield of roughly -0.9%. That is the reverse of what the Favorite–Longshot Bias normally produces, and it immediately suggested that 2025 had behaved in a very atypical way.

Normally, favorites deliver better expected results than longshots because bookmakers do not distribute their margin evenly across all prices and higher odds usually carry a heavier share of the overround.

To see whether 2025 was just a strange outlier or something more meaningful, I expanded the analysis. Using the same methodology—Pinnacle closing odds and flat stakes—I went back through all ATP main-draw matches from 2010 onwards.

The Full Evidence: 2010–2025, 39,886 Bets

By placing the 2025 anomaly inside a sample of more than 15 seasons and close to 40,000 matches, the broader picture becomes clear: the Favorite–Longshot Bias is a very stable feature of tennis betting markets.

Most bettors, especially those familiar with Pinnacle’s research on market efficiency, already know the basic idea: favorites tend to be priced with thinner margins, while longshots carry a larger share of the bookmaker’s edge. That means longshots are usually pushed further away from their fair price. The goal here is not to re-explain the concept, but to measure it directly using real ATP data and show how strong it is over long periods.

Data and Method

To build a clean dataset, I applied the following rules:

- Matches: All ATP main-draw matches from 2010 to today

- Odds: Pinnacle closing prices (from tennis-data.co.uk)

- Staking: 1 unit per bet, flat stake

- Cleaning: Matches where the first set was not completed were removed (as these bets would be void in Pinnacle and most of the bookies), along with minor data errors

- Final sample: 39,886 matches

On this dataset, I tested two simple strategies:

- Bet every favorite

- Bet every underdog

Both across the full sample.

The outcomes were:

- Favorites: –2.0% yield

- Underdogs: –5.6% yield

Even with no selection or filtering, favorites clearly perform much better than underdogs. Both are negative—as you would expect in an efficient market—but the gap between –2.0% and –5.6% is large. This already confirms, at a high level, that the Favorite–Longshot Bias is present in ATP markets.

Breaking Down the Underdogs

To understand how the margin behaves across different price levels, I divided all underdog bets into 20 equal groups. Each group contains around 1,994 bets, ordered from the lowest odds to the highest.

This lets us see how performance changes as prices rise, instead of treating all underdogs as one single category.

The pattern is very clear:

- Small underdogs (roughly 2.0 to 3.0) show mixed results, with some groups even slightly profitable.

- From around 6.0 upwards, performance turns sharply negative.

- As odds increase, yields fall faster and faster.

- The highest odds produce some of the worst long-term results in the entire dataset.

This is the Favorite–Longshot Bias in its pure form: The higher the odds, the larger the embedded margin, and the worse the long-term outcome for blind betting.

It’s worth stressing that this is a bookmaker-market effect. On betting exchanges, where people trade directly with each other, this structural bias does not exist.

Closing Thoughts

Based on my own analysis of nearly 40,000 matches, two clear conclusions emerge:

- The Favorite–Longshot Bias is very much alive in ATP tennis.

Bookmakers load most of their margin onto longshots, which makes favorites systematically cheaper and underdogs structurally expensive. - Even though value can sometimes be found at high prices—especially with strong information or good models—relying heavily on big underdogs is mathematically damaging over time. The margin grows quickly as odds rise, and the long-term results make this impossible to ignore.

This does not mean longshots can never be good bets. It means that any value in that part of the market has to be very strong just to overcome the built-in disadvantage.

Anyone trying to build a serious, data-driven betting approach in tennis needs to understand this structural imbalance. Longshot opportunities will always exist, but the long-term numbers show that this part of the market must be treated with extreme caution and strong justification